It’s not always easy to distinguish between vocabulary and the other building blocks of adolescent literacy. For instance, in order to comprehend text, one has to know what the words mean. And while word study focuses on sounding out and recognizing words, it also involves the learning of new vocabulary.

However, because vocabulary plays such a key role in reading, and because so many students need effective vocabulary instruction, reading experts often treat it as a discrete category on its own.

Researchers have found that by the time children enter kindergarten, they already exhibit vast differences in the numbers of words they know. According to the oft-referenced research by Hart and Risley, children of relatively affluent, well-educated parents typically arrive at school with a working vocabulary of 5,000 or so words, while low-income kids often enter school knowing only 2,500, and that gap tends to widen over the years unless schools make special efforts to close it.1

This research commonly referred to as the 30-million word gap has recently been challenged by Douglas and Linda Sperry as they posit that “differences in the number of words children hear cannot be predicted by socioeconomic standing alone.” 2

The Sperry study is important in that it challenges educators to look beyond home circumstances as a basis for a student’s literacy levels and focus instead on enriching the “approaches to language achievement” in their schools and classrooms.

However, the debate doesn’t deny that “the gap exists and remains enduring. Our increased understanding of the research evidence shows that the gap may be smaller than judged by Hart and Risley, but that many children come to school with having heard millions more words and having experienced many more rich interactions with parents and caregivers.” 3

But It’s not just the number of words that matters. Students also need to know different kinds of words, ranging from the most common everyday terms to those that are more unusual and academic.

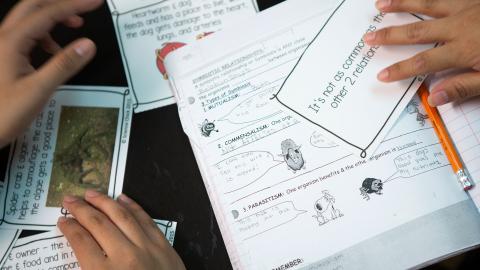

To help teachers decide where to focus their efforts, researchers Isabel Beck, Margaret McKeown, and Linda Kucan describe three different categories — or “tiers” — of words in their book, Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction. Tier 1 includes common, everyday words that most kids know and probably don’t need to be taught (e.g., house, anyway, other, and so on). Tier 2 includes words that might not come up so frequently at home and among friends, but which do often appear in schoolbooks, newspapers, formal documents, and the like (e.g., residence, regardless, and alternative). And Tier 3 includes rarely used words (e.g., billet, hitherto) and terms used mainly in specific content areas (e.g., isotope, metonymy).

Literacy experts advise teachers to focus their vocabulary instruction mostly on Tier 2 words, and to teach Tier 3 words only when they come up (such as in preparation for a chemistry unit on elements and isotopes).

Further, researchers argue that the most common approach to teaching vocabulary — providing students with a word list on Monday then quizzing them on Friday — doesn’t work. According to Sperry, “language is richer than vocabulary alone.” Kids don’t really learn and remember words unless they see them many times in print, use them many times in their classroom discussions and written texts, and continue to see, hear, and use them subsequently.

Vocabulary instruction: the basics

Make vocabulary study a regular activity.

While vocabulary instruction is a regular part of the curriculum in most elementary schools, it tends to tail off in the upper grades. However, students continue to need help throughout grades K-12, especially if they’re trying to make up for limited vocabulary learning in the pre-school years. That’s not to say that vocabulary lessons should take up entire class periods, though — regular, 10-15 minute activities will be far more effective than a handful of hour-long sessions.

Teach more by teaching less.

Not only is it ineffective to make students memorize random words, but it’s counter-productive to give them too many words at one time. Given that some students are many thousands of words short of a decent vocabulary, teachers may be tempted to assign them long word lists to study. However, that’s more likely to overwhelm kids than to get them to learn and remember anything. In the long run, teachers can have a greater impact on vocabulary by giving students repeated exposures to 5-10 useful new words every week, rather than by drilling them on 20 or more words at a time (most of which will be forgotten fairly quickly).

Use new vocabulary in the classroom.

Researchers have found that it usually takes 10-15 exposures for new words to stick in people’s minds, and those words stick better when used in the flow of conversation, rather than studied as part of a list. When choosing new terms for study, teachers should look ahead to see what students will be reading about and discussing in the coming weeks, and after teaching the words’ meanings, they should reinforce the new vocabulary by using it often and encouraging students to use it themselves.

Teach synonyms, antonyms, and alternate meanings of words.

Students will have more success learning and remembering words if they study them along with clusters of related terms. Further, teachers should point out those words that mean different things in different contexts (e.g, the use of the term reaction in chemistry and its use in everyday conversation), helping students to appreciate the nuances of the language.

Model what to do when students come across new words.

Reading teachers often advise students to look for “context cues” to help them make sense of new words. In other words, students are supposed to figure out what the rest of the sentence or paragraph means and then make an educated guess as to the term in question. But most students need more explicit guidance than that. Teachers may want to model exactly how to look up the word in a dictionary, for example, or to search for the term on the Web, in order to find a few more examples in which the word is used in a sentence.

Teach specialized vocabulary in the content areas.

Teachers in the content areas have a responsibility to teach the specialized terms (e.g., mitosis), or specialized meanings of common words (e.g., mathematicians’ understanding of the words square and root), that students are about to encounter in class. Periodically, they ought to look ahead in the textbook or syllabus to see which terms will be used, check to see whether students know those terms already, and explain those as needed.

More resources

Visit our library of essential articles on vocabulary instruction.

Education Next offers an overview of vocabulary instruction and strategies

The ReadWriteThink website, hosted by the National Council of Teachers of English and the International Reading Association, features many lesson plans related to vocabulary instruction.

Wordsift is a terrific, free website that lets teachers analyze vocabulary in a given text before teaching it. For example, the teacher can cut and paste a textbook chapter into the website and it will highlight the most frequently used words, highlight the “academic” terms, suggest clusters of synonyms, and more.

Middleweb offers research and classroom strategies to effectively use Word Walls in Middle School Classrooms.

Endnotes

1 Hart, T., & Risley, B. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes

2 New Research Ignites Debate on the ‘30 Million Word Gap’

2 It’s time to move beyond the word gap

3 How To Develop Vocabulary in the Classroom