As we begin to think about adolescent readers and effective literacy instruction, it’s important to consider what we know about how we learn to read and where adolescent readers, writers, and thinkers fit into the continuum of reading development.

Reading Is Complex

There is no gene for reading. And unlike the acquisition of oral language, reading does not develop naturally. Instead, our brains have evolved over time as our writing systems have developed. Our brains are flexible and adaptable, which researchers have long believed but have now witnessed through fMRI brain imaging of readers. Collected images highlight not only the brain’s ability to reroute around underdeveloped or underutilized areas of the brain, but the positive impact of targeted instruction and intervention as well.

Long before fMRI images were available, cognitive scientists began theorizing about how our brains process, store, and retrieve information. Since its inception, cognitive theory has laid the groundwork for many of the most frequently applied models of reading by presenting reading as a set of components that work together to enable a reader to gain meaning from text.

The Simple View of Reading

Gough and Tunmer’s (1986) Simple View of Reading model is perhaps the mostly widely known and adapted model. It attempts to simplify the complex interactions between lower-level linguistic processes (e.g., word-level processes such as letter-and-word recognition) and higher-level cognitive processes (e.g., use of background knowledge, monitoring comprehension, inferencing). It also highlights the difficulties in becoming a proficient reader if your decoding skills and language comprehension skills are not fully developed. As Gough, Hoover, and Peterson (1996) write, “Both skills are necessary; neither is sufficient.”

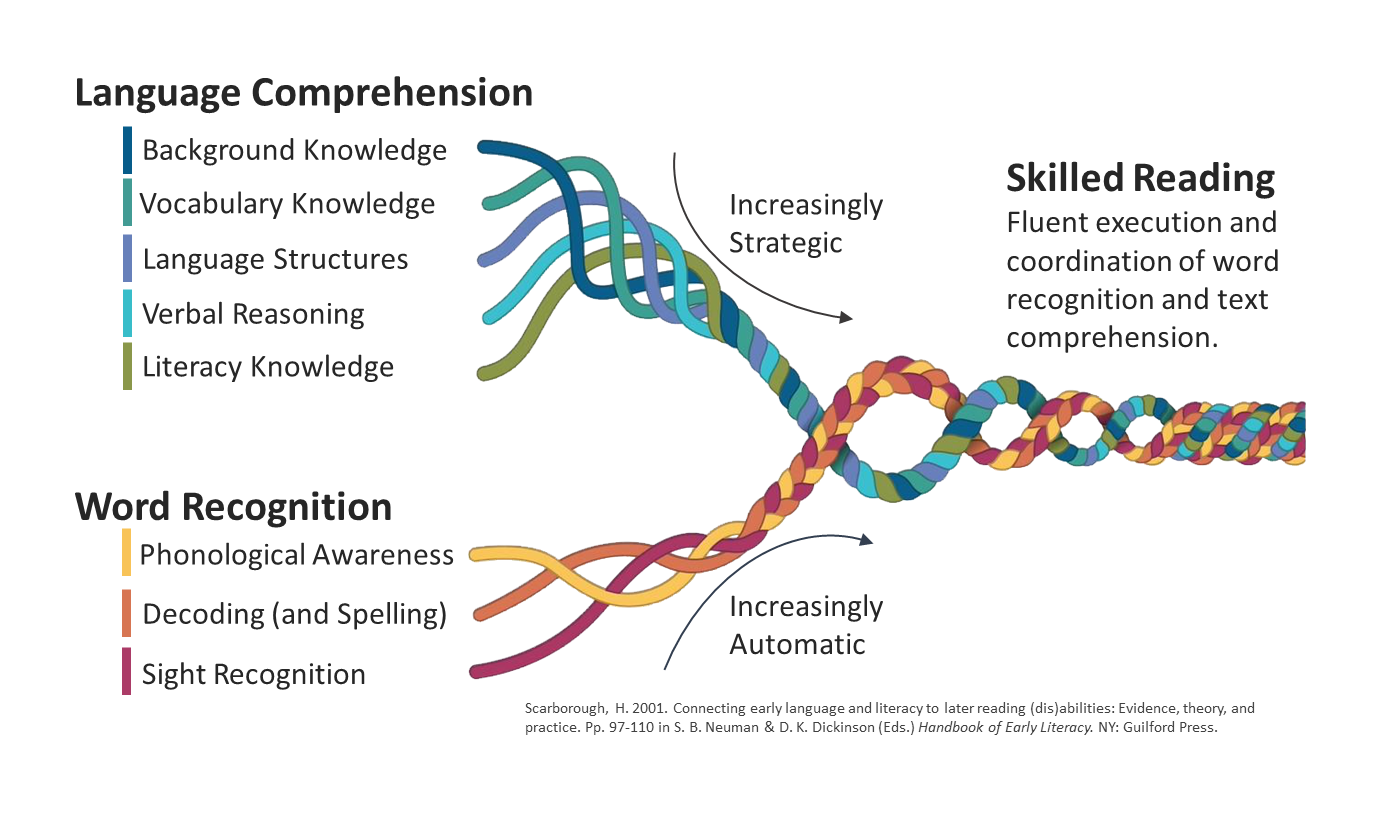

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

A more recent addition to the component skill models of reading, Scarborough’s Reading Rope (2001), expands The Simple View of Reading’s components and once again demonstrates the complexity of helping students become skilled readers.