Do your students have difficulty monitoring their own understanding while reading, making sense of unfamiliar content or specialized terms and concepts, or making connections within and across readings? If so, they are not alone. Even students who have mastered the written code and can read fluently may struggle to make sense of what they read in the middle or high school grades.

Over the years, researchers and educators have developed many comprehension strategies that students can use before, during, and after reading to help them make sense of a text. Numerous research studies have found specific comprehension strategies to be effective, helping students to make significant and lasting gains in their ability to understand texts they read in and out of school. But strategy instruction alone will not improve your students’ reading comprehension and critical thinking. A balance of explicit strategy instruction with authentic applications to reading and writing (Duke & Pearson, 2002) and scaffolded discussions is required to really move the needle.

The Power In Thinking Aloud

During explicit strategy instruction, teachers need to share: What is the strategy that we are learning? How do I employ this particular strategy? Why do I use this strategy? When is it a good time to use it?

Chris Tovani, a well-known author and high school English teacher, writes, “When teachers make the invisible mental processes visible, they arm readers with powerful weapons. I stop often to think out loud for my students. I describe what is going on in my mind as I read. When I get stuck, I demonstrate out loud the comprehension strategies I use to construction meaning.” Let’s watch as she demonstrates her thinking to her students.

Key instructional Ideas

Before reading

Help students tap into what they already know about the material. It doesn’t necessarily occur to students that their existing knowledge, experience, and preconceptions will have an impact on their reading. Before assigning them to begin a new book, chapter, or other text, give them a chance to review what they learned from previous assignments, to write down any important questions or points of confusion related to the topic, and to discuss any assumptions or opinions likely to influence their understanding of the material.

Provide important background information. For example, use vocabulary, specialized terminology, context, and content that students might not know but which they’ll need in order to make sense of the text.

Preview the text. Encourage students to glance through the material before they read it in order to get a sense of the overall length, tone, and direction of the piece. Point out any headings, subheadings, and other information about the structure of the text that might be useful, or have them discuss or write down predictions as to what the text is likely to say.

During reading

Help students monitor their own comprehension. Skilled readers may already know that they can stop and review paragraphs to make sure they understand them, re-read confusing passages, look up a word in a dictionary, or jot down questions as they go, but some students need to be taught these “fix-up” strategies.

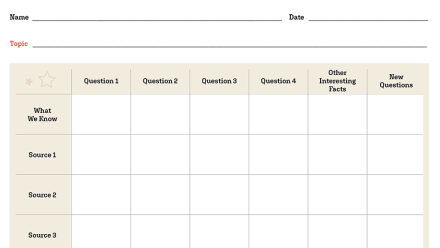

Teach students to take notes and to draw visual representations of what they read. It may not occur to students that they can read with a pen in their hand, making notes on paper or, when appropriate, on the text itself. Research has shown that using graphic organizers can be especially helpful in boosting reading comprehension. They can include any kind of outline, annotation, mapping out of text, or other visual representation of what a text means, how it connects to other material, and what questions it raises.

After reading

Teach students to summarize accurately. Summarizing texts can help both to clear up any confusion about the meaning of a text and to secure it more firmly in students’ memories. However, it can take a lot of practice to become adept at writing concise, accurate summaries that focus on main points and skip extraneous information. You can begin by modeling for your students how to formulate oral and written summaries, including how you identify key points, paraphrase them, and condense them. Your students can work on their own with relatively short, simple passages before going on to summarize longer and more complicated texts.

Discuss the text. Probably the most important comprehension strategy of all — but one that is surprisingly rare — is to give students frequent and extensive opportunities to discuss what they’ve read. When students do engage in high-quality text-based discussions, they tend to come away with much clearer and more nuanced understanding of the material.

Keep the goal in mind!

Explicit teaching of reading comprehension strategies has value but not at the expense of content. Choosing fewer strategies to implement and giving students multiple opportunities to use them, perhaps even across content areas, avoids less class time devoted to learning strategies and more time to learning content. The power of graphic organizers is not in filling them out but in using them as a springboard for discussions.

Active Discussions Spark Critical Thinking

Is your classroom filled with student discussions? If not, why not? An important aspect of active learning is discussion, but sometimes the pressure to have concrete evidence (e.g., a filled-out organizer, written assignment, etc.) of students’ comprehension can breed a reluctance to use students’ discussions as evidence of their growing understanding. Yet, we have moderate evidence that sharing and listening to others’ reactions and questions about what they are reading increases students’ understanding of text.

Successful comprehension or “thinking” instruction frequently provides opportunities for students to discuss with partners, small groups, and their instructors. We need to pose thought-provoking questions, keep the conversation focused, guide it through lulls, and help students to learn and abide by classroom norms and rules (e.g., turn-taking, respecting others’ opinions, staying on point). When students do engage in high-quality text-based discussions, they tend to come away with a much clearer and deeper understanding of what they have read.

Consider how many opportunities students have to discuss their ideas with one another in your class. If it turns out you are asking most of the questions, then you are doing most of the thinking, not your students.

Related Resources

Comprehension

Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach?

Blog: Shanahan on Literacy

What Does It Take to Teach Inferencing?

Comprehension Writing